-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

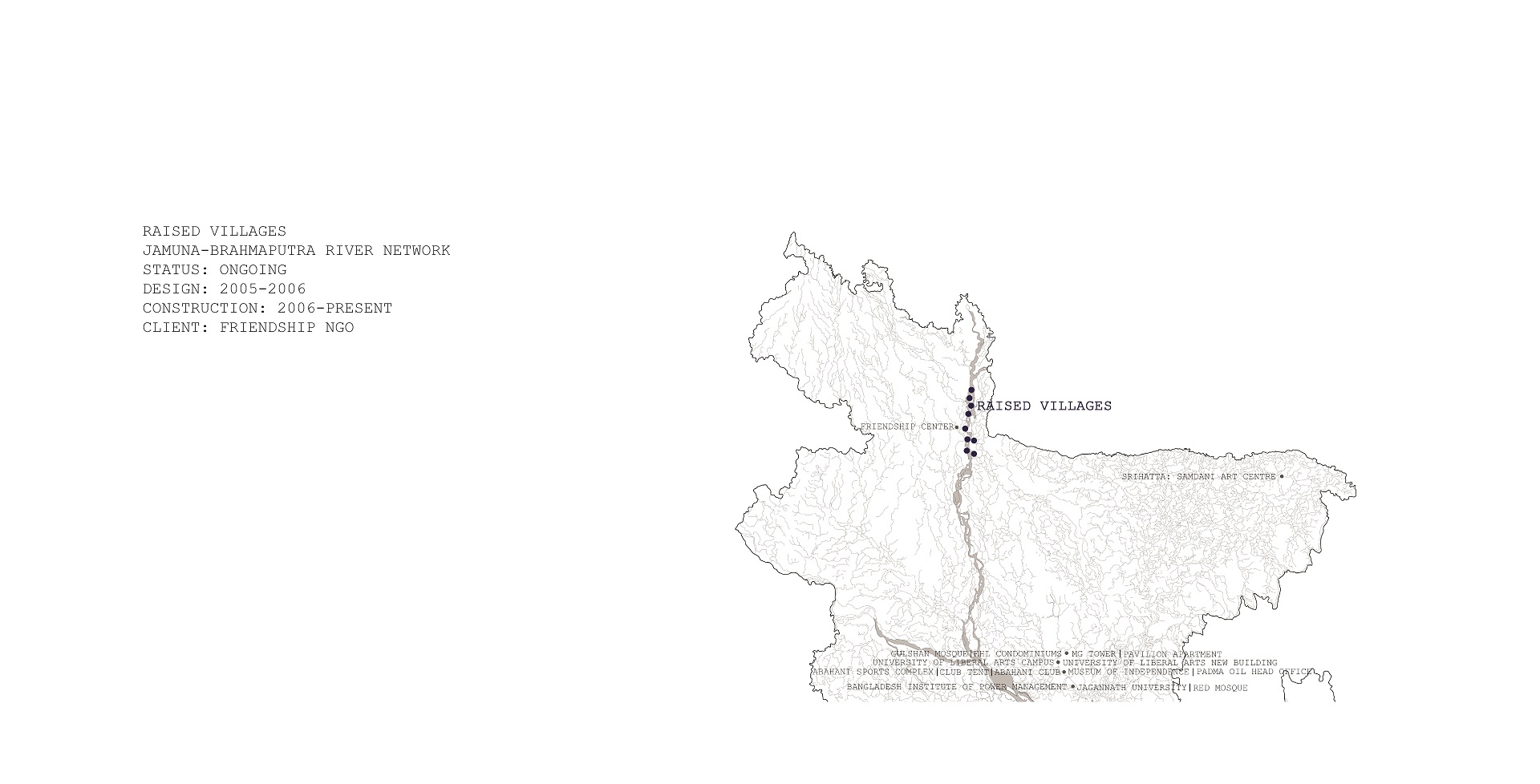

It was in 2005 that Kashef Chowdhury/URBANA started working with the NGO Friendship in climate action projects. The first of these addressed the plight of migrant population in riverine islands or ‘char’ by creating repeatable landforms to house entire villages above the level of yearly floods by simple dig-mound. This was chosen over raising individual houses on stilts because:

-

In Bangladesh stilt houses exist only in the hill-tracts where surface run-off in the slopes passes below the houses. But this typology does not exist in fierce flood plains in the delta because of its impracticality in high current settings.

-

Any foundation or point load of a stilt will attract whirlpools, consequently sucking out soft silty soil from around the support structure. Many examples of failed structures exist in the rivers because of this reason peculiar to the alluvial delta.

-

A foundation that will actually hold in this scenario will be forbiddingly expensive, like piers in a bridge.

-

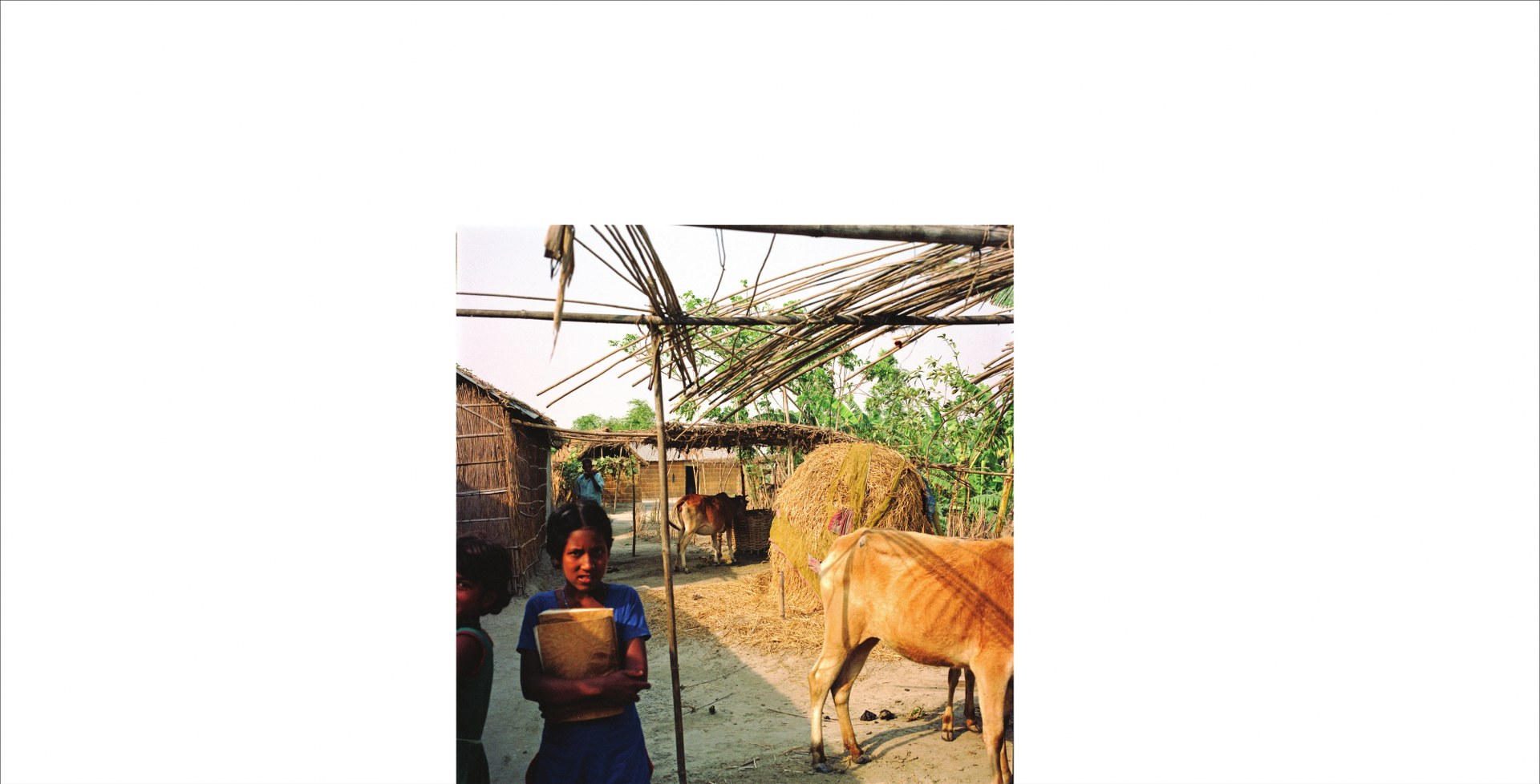

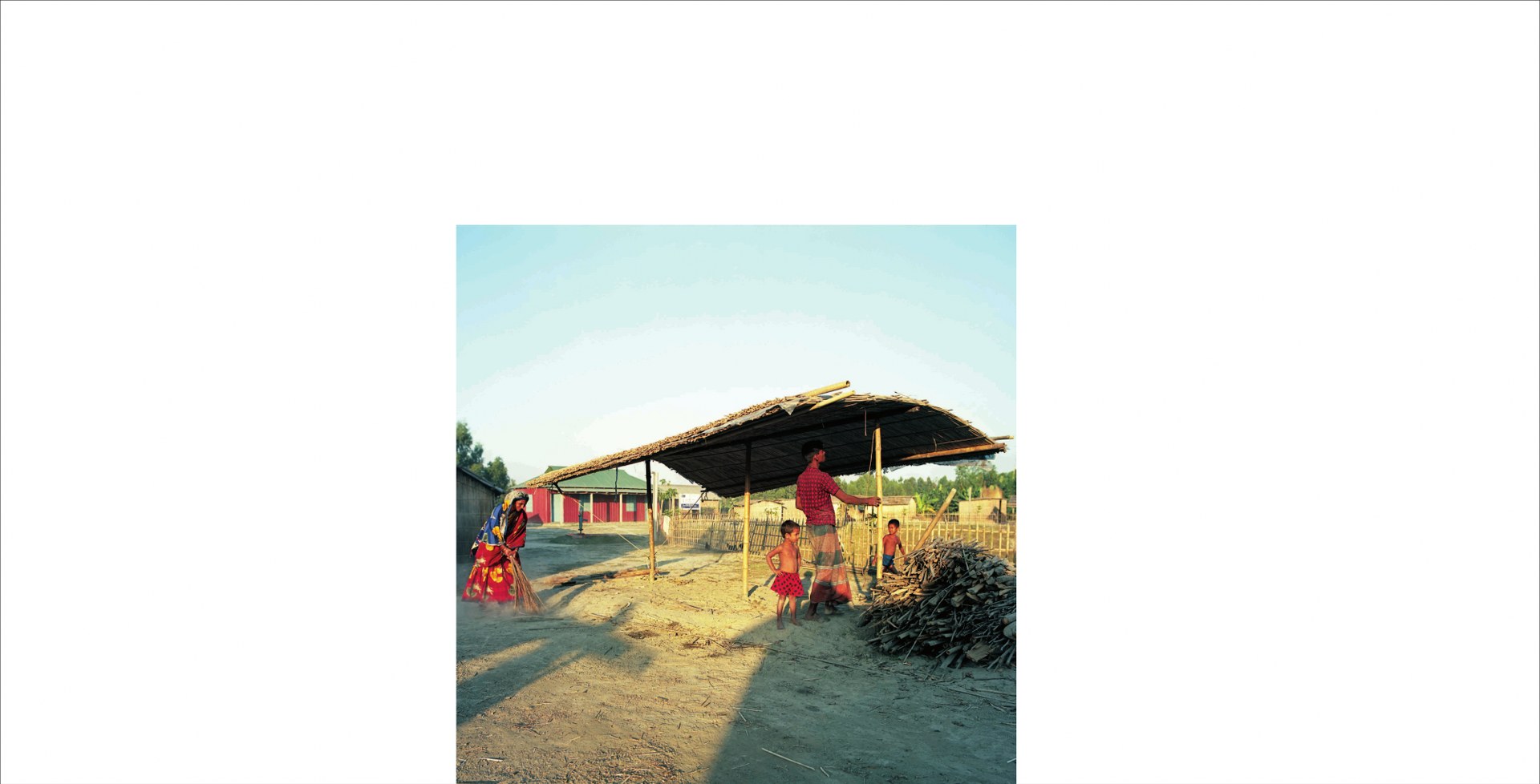

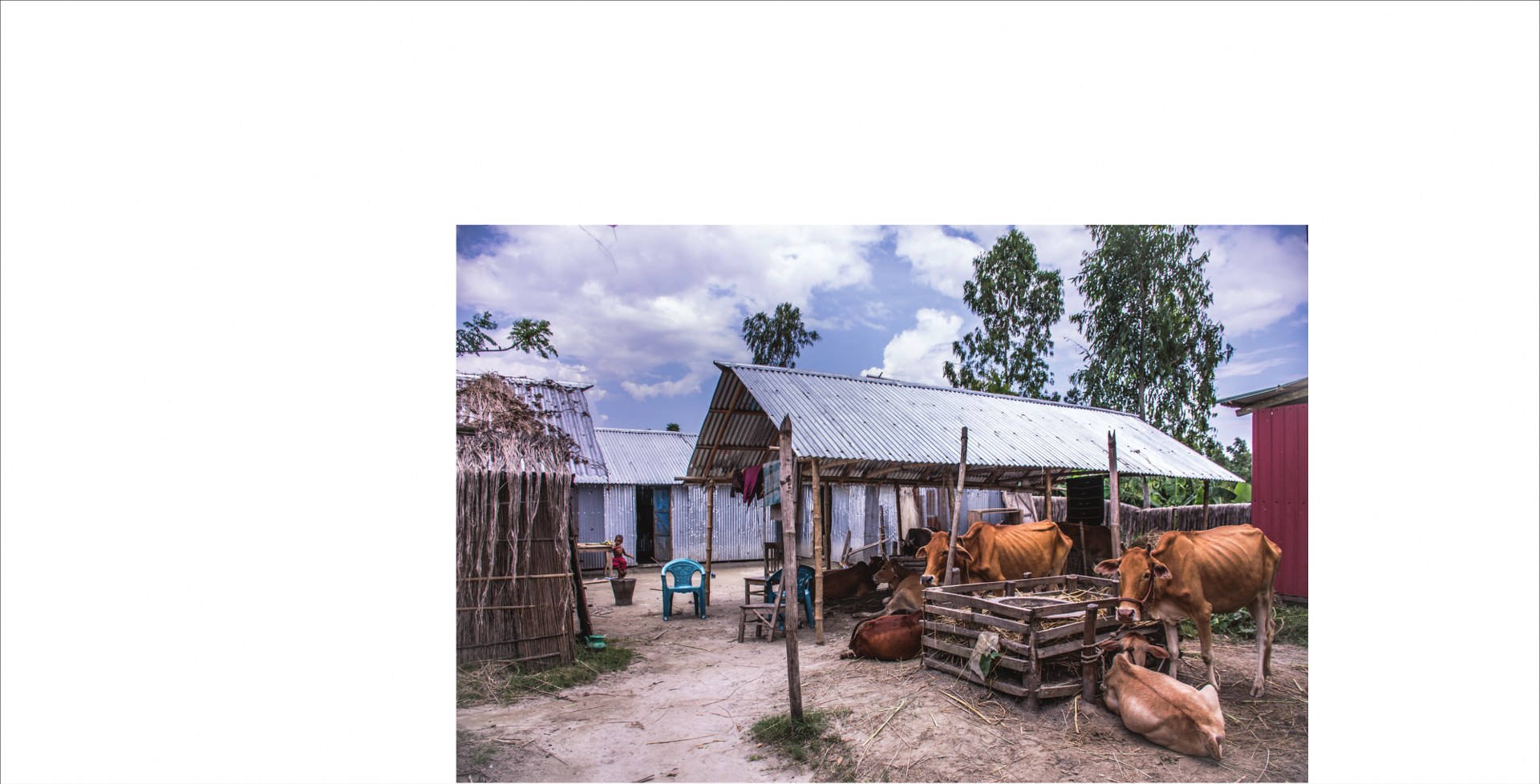

Ladder only access means there is no provision for saving cows and goats when the flood arrives. A cow or a goat is possibly the only asset of a villager in the char and the stilt house solution cannot cater to this basic need.

-

A raised house is a risky proposition for the safety of toddlers and babies who constitute majority deaths during floods by accidental falls into the current.

-

Floodwaters may not recede for as much as two months and so extended living in the constricted space of a stilt house is not preferable to the dry land of a raised island.

-

-

Therefore any design that has not researched or addressed the above must be considered impracticable, no matter how well it is marketed.

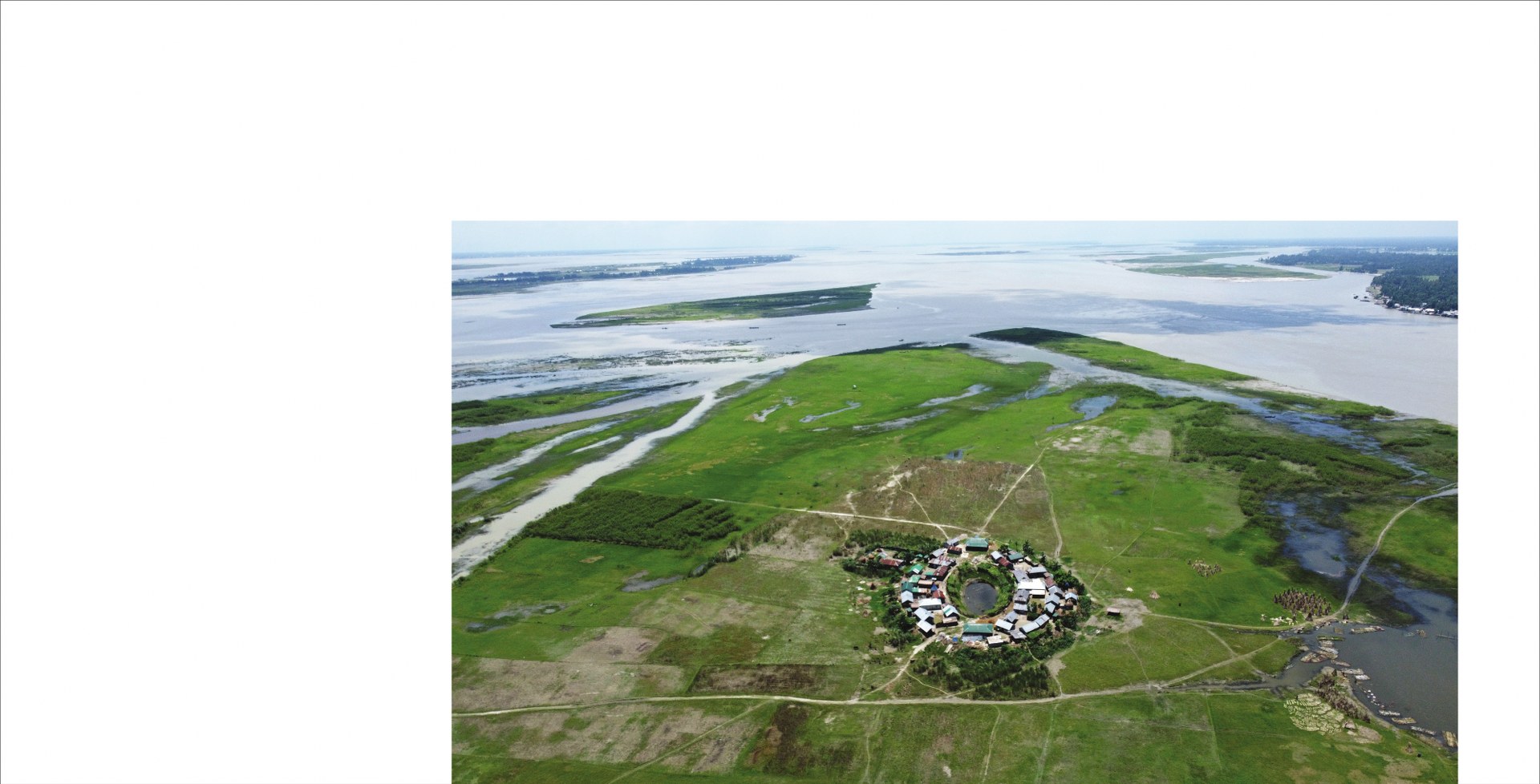

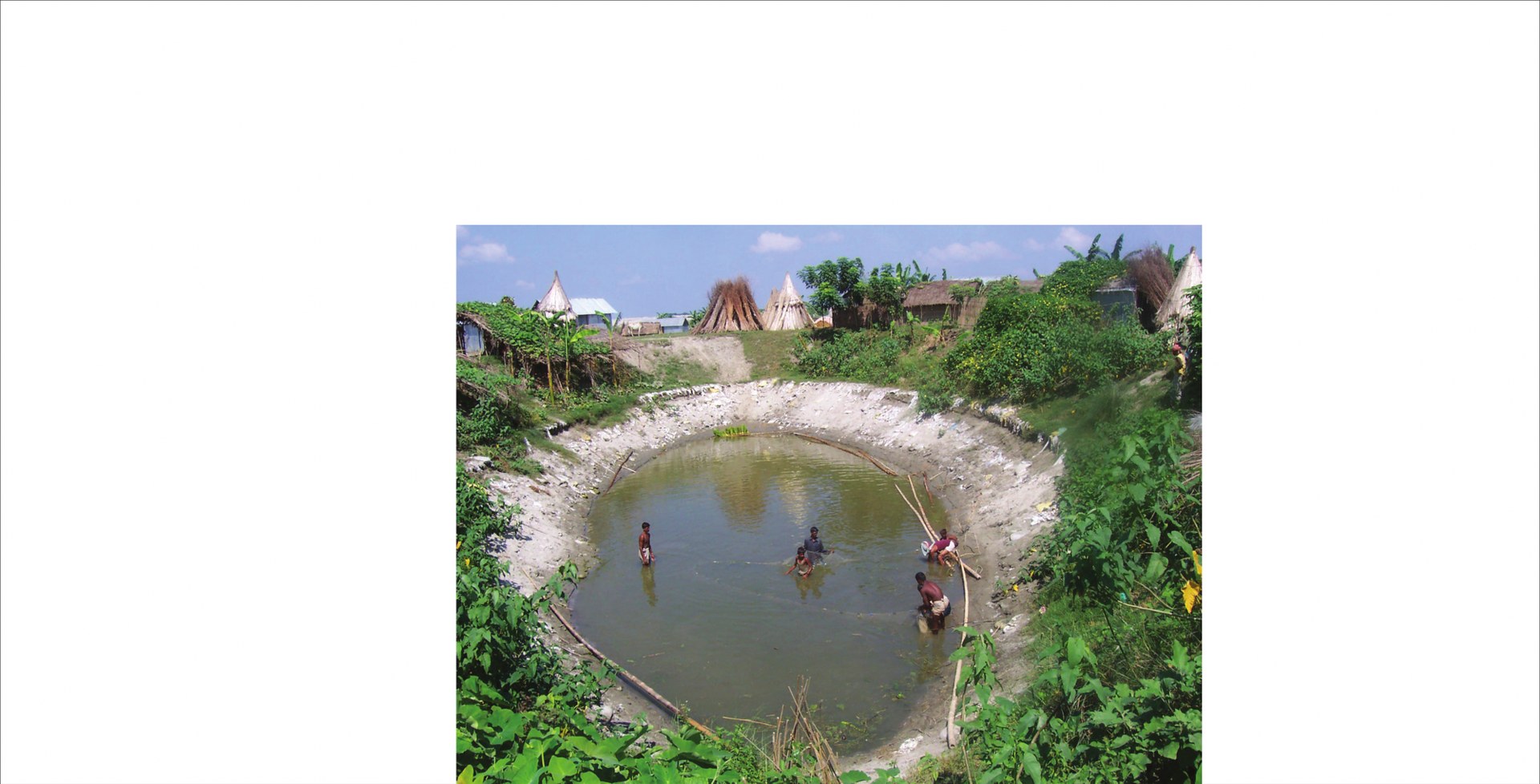

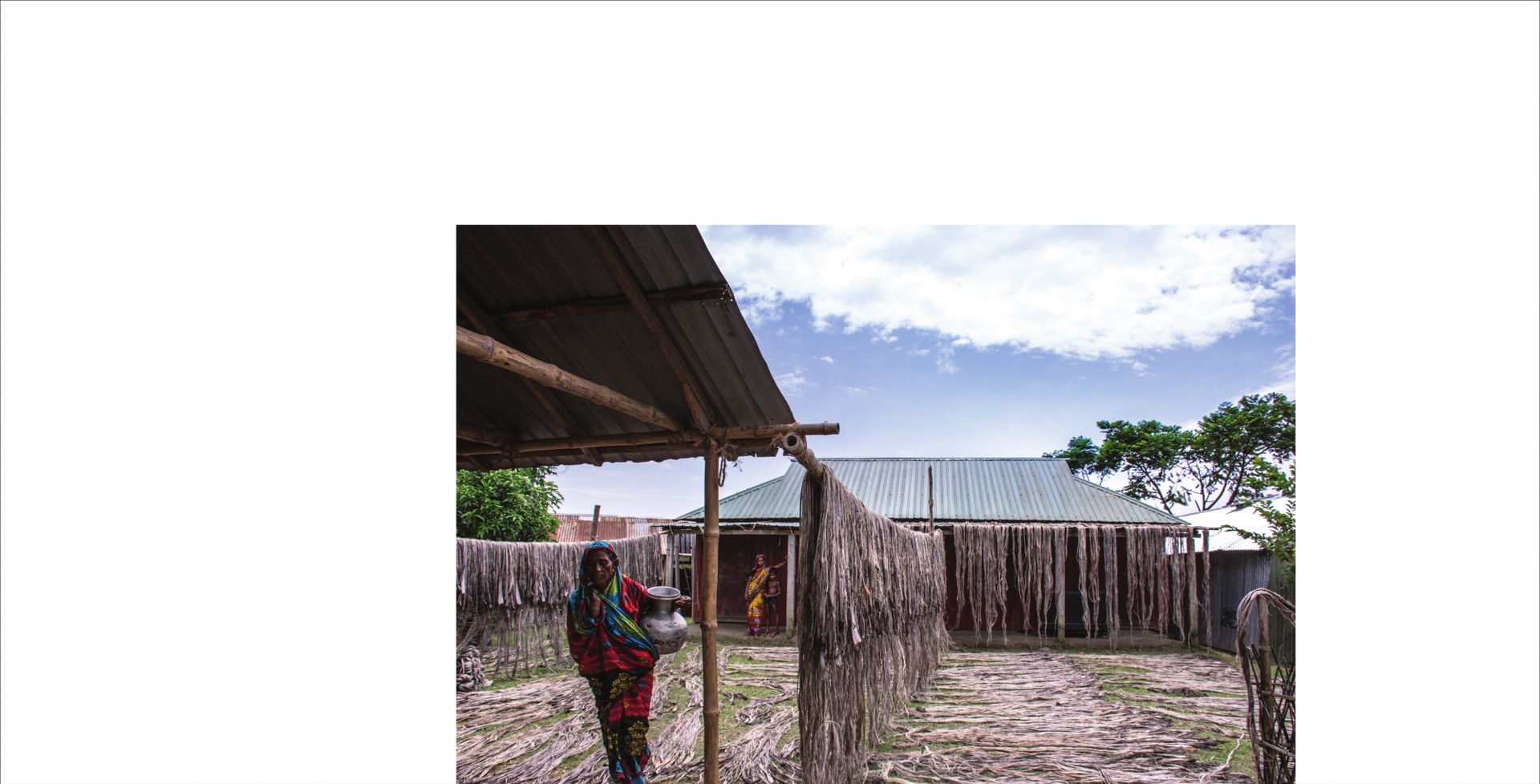

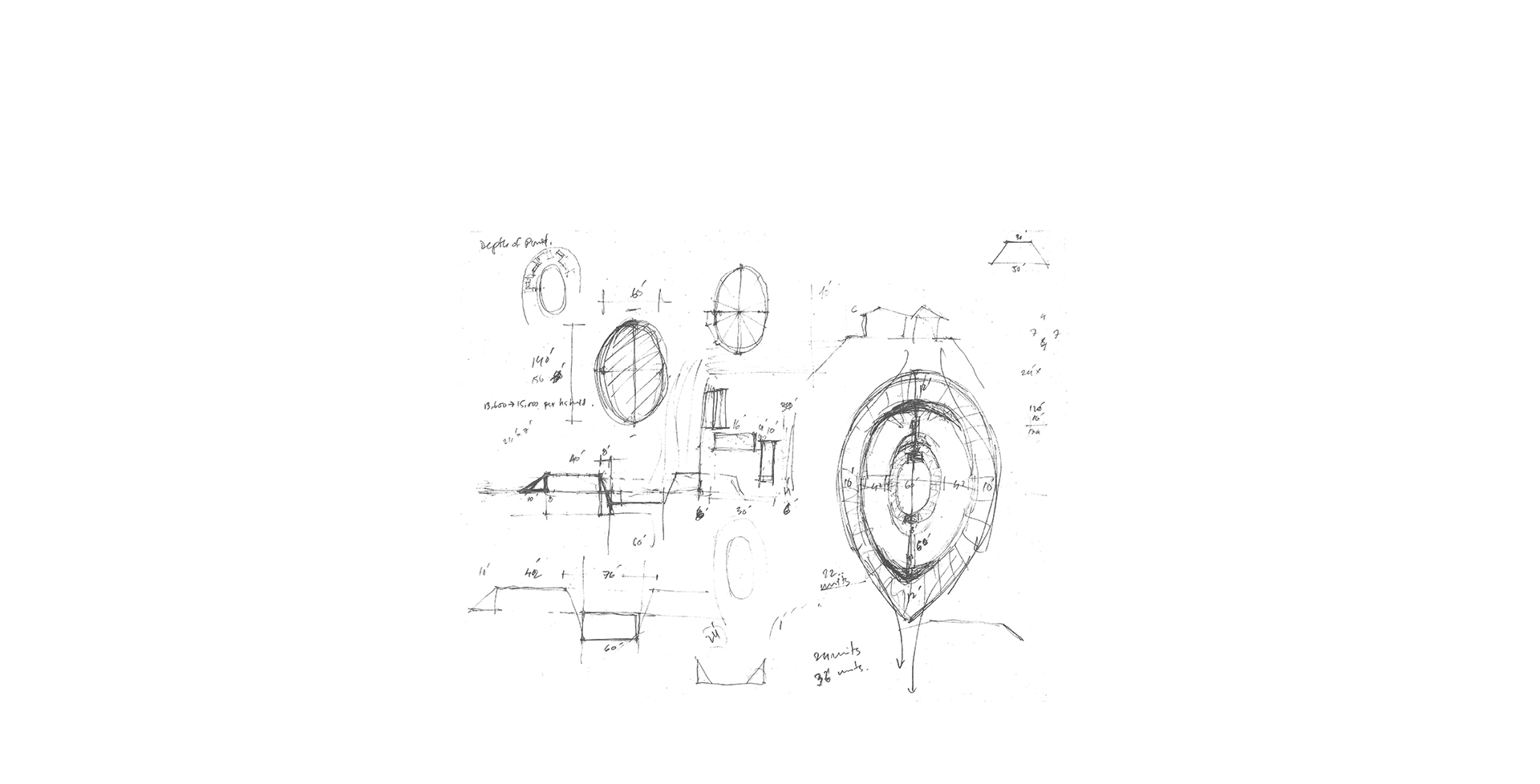

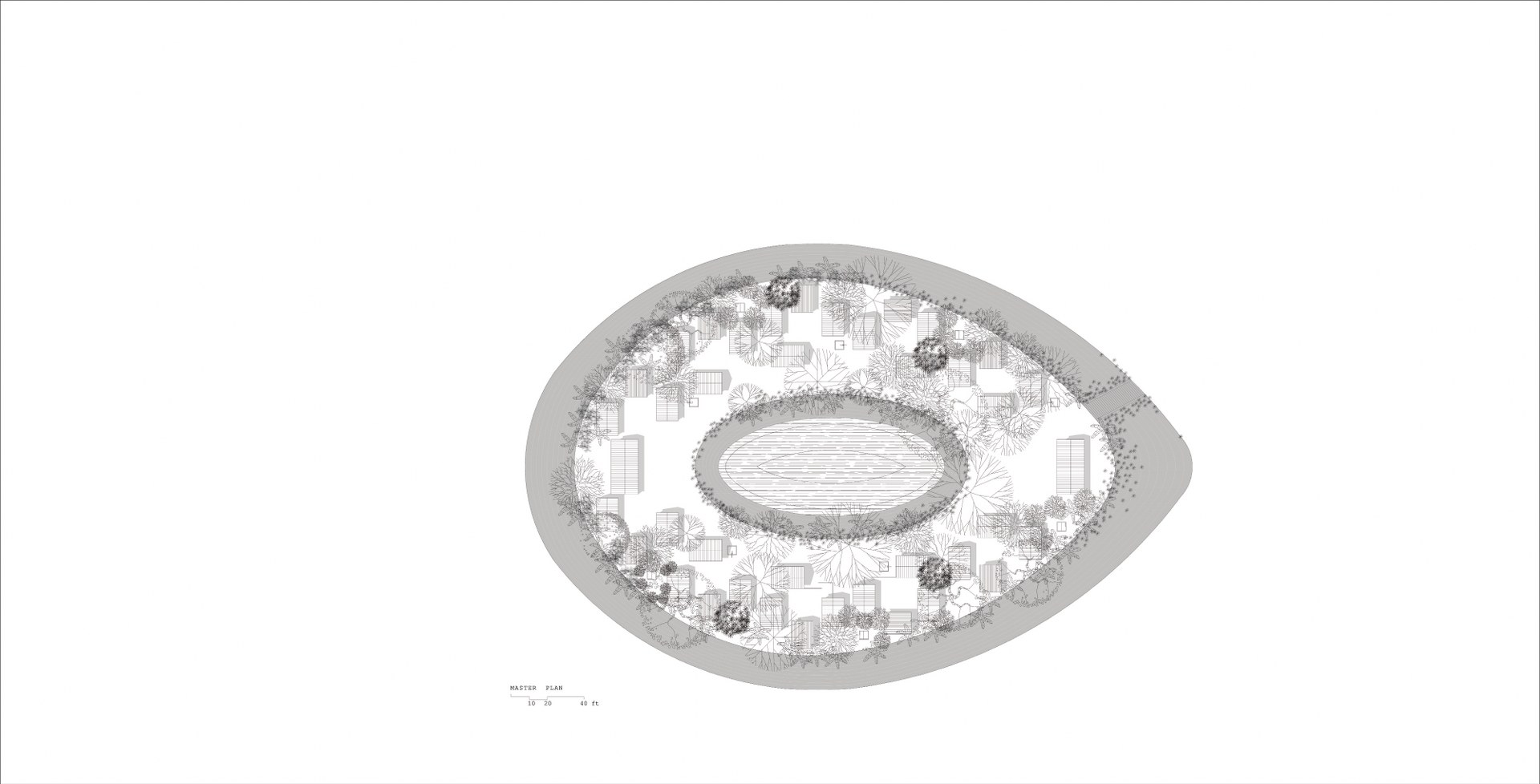

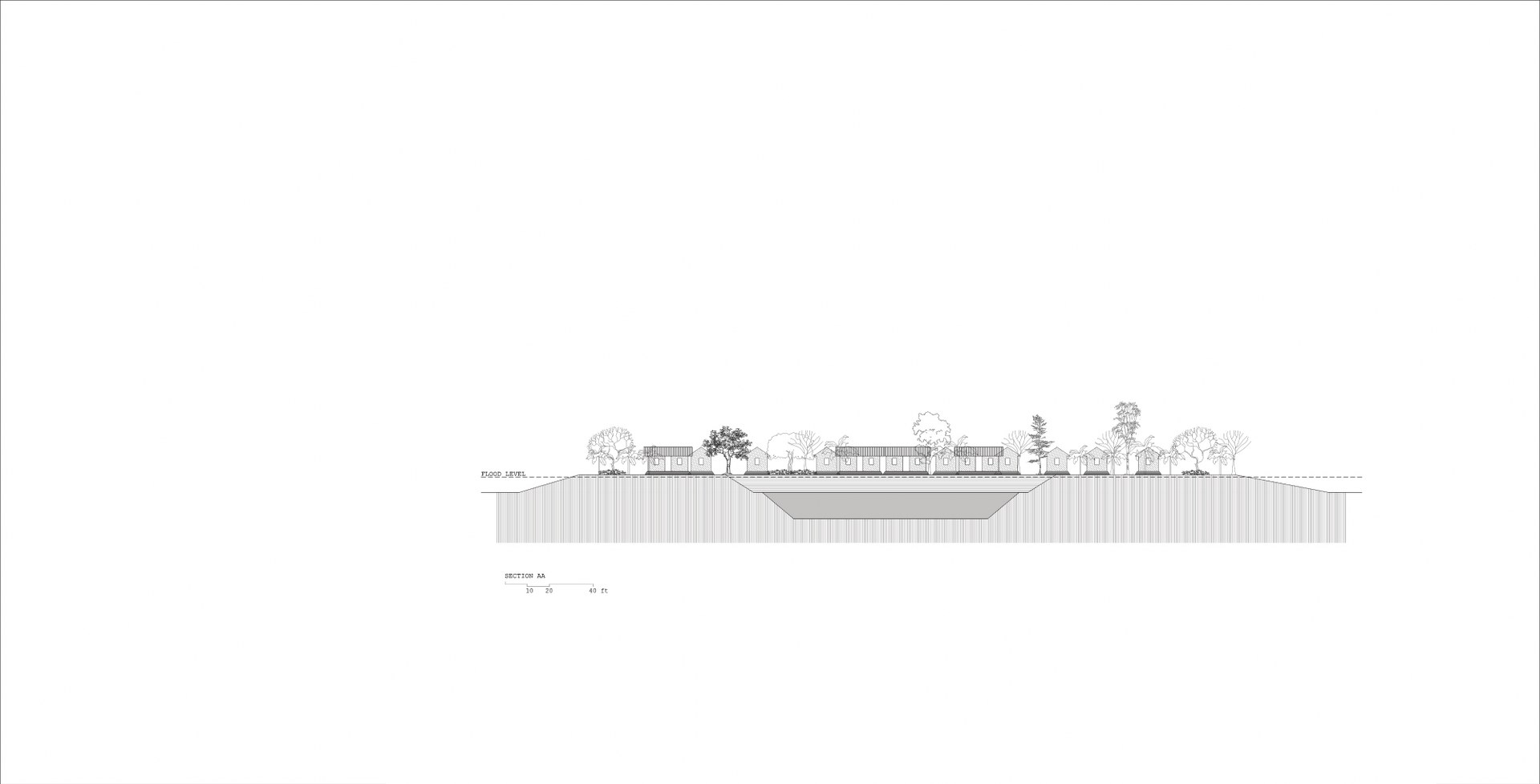

URBANA’s design resulted from the study of maps and aerial observation of river islands, whose ‘comet’ shapes are formed by the flow of water and alluvial deposits. And so resulted the teardrop shape of the island, with the addition of a pond in the middle, which could hold rainwater for use during floods and be used for fishery under normal conditions.

The masterplan of the settlement was prepared by observation and study of notions and wisdom of placement of houses and courtyards in traditional villages. An interesting outcome was that many times the villagers did follow the masterplan but sometimes deviated from it, opening up or creating more privacy in courtyards.

Instead of fighting it, the people in these liquid landscapes live with the water. The architect’s intention was similarly to design with the flow of the river and create a settlement through a self-help and interactive process.

-

-

-

-

- Climate Change

- Built/Unbuilt

- Exhibitions

- Practice

- Publication & Lectures

- Info

- News

- Education & Institution

- Art Spaces

- Health & Leisure

- Live, Work & Industry

- Spiritual

- Museums

- Sports

- Rural - Urban